By Catherine Owen

At first glance, the two issues appear unconnected: in one, China and the US are engaging in diplomatic and military brinkmanship for influence in the South China Sea; in the other, Central Asian governments are embracing with open arms the Chinese vision for a 21st Century Silk Road across their territories. In the first, China argues it is countering a deeply unfair containment policy enacted by a United States afraid of a rising China; in the second, China claims it is bringing ‘new positive energy into world peace and development’.

These contrasting displays of international politics are linked through an ambitious Chinese vision for improving global trade routes for its products, known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), with the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) stretching through the South China Sea and around the Horn of Africa, and the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) extending across Central Asia. OBOR will not only provide important infrastructural construction contracts for Chinese companies in an ailing domestic market, but also increase ‘connectivity’ and ‘cultural exchange’ with transit countries in what has been advertised as a ‘win-win’ situation for all concerned. But what are the consequences for those countries to the west of China of this increased tension and display of power in its east?

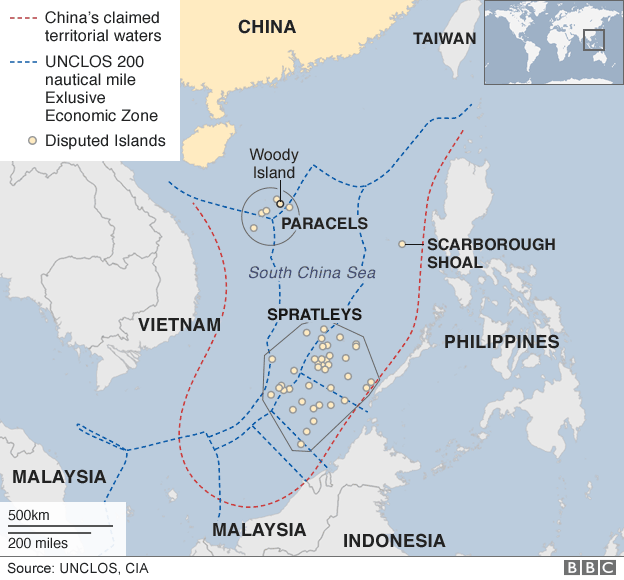

Tensions in the South China Sea have been brewing for years, but in the last six months they have reached new heights. The roots of the tension lie in a series of disputed islands and rocks located in waters rich in natural resources and constituting important maritime trade routes, which are variously claimed by China, Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Taiwan. China’s smaller neighbours argue that China’s claims far exceed that which it is entitled to under international law. However, China has continued to develop the disputed areas: the Spratly Island Archipelago now hosts China’s most important outpost in the South China Sea, including a sizeable airstrip and harbour.

Inter-regional relations are becoming increasingly strained. On 23rd May the US lifted a longstanding embargo on exporting weapons to Vietnam. Although it was portrayed as a step towards ‘normalising’ relations after the Vietnam War, Chinese officials and Western analysts view the decision as a move to counter the growing Chinese influence in the South China Sea. Malaysia has accused China of intimidation through incursions into its waters, and the Philippines have taken China to the Permanent Court of Arbitration over the legality of China’s claims in the South China Sea. China has stated it will ignore the outcome, which is due imminently.

China’s island building strategy not only seems to be about fishing rights and natural resources, but also about countering US power in the region, which it sees as illegitimate. A key aim is to build infrastructure able to monitor US movements more closely and respond faster in the case of encroachment into what is considered Chinese space. Citing US plans to install a Thaad Anti-Ballistic System in South Korea, which, although primarily aimed at North Korea, can also extend into much of China, Chinese military officials have stated that the deployment of nuclear submarines in the South China Sea is inevitable. The US Defense Secretary, meanwhile, said the US would engage in a campaign of ‘gentle but strong pushback’ against China.

This fraught situation contrasts greatly with China’s relations with the Central Asian states. In a region where the US seems to be disengaging since the withdrawal of the majority of forces from Afghanistan, Chinese political elites have been ramping up engagement. Three years ago, China floated the idea of reviving the ancient Silk Road across Central Asia, an idea which corrupt and cash-strapped Central Asian governments have been quick to take up. Consequently, China-funded infrastructural projects across the region have proliferated. In contrast to the South China Sea, then, Central Asia presents itself as a playground for China.

What are the consequences of the volatile relations in the South China Sea for Central Asia? Will the region take on a greater significance for China in light of its difficulties to its east? Two considerations are important here, a material and a discursive one. Firstly, China could make a greater effort to establish itself in Central Asia as its attempts to exert control in the South China Sea are thwarted by the US. If the Maritime Silk Road project is jeopardised through US containment and soured relations with ASEAN states, it is likely that China will redouble its efforts in the west. This could mean both increased economic and political leverage by China in Central Asia.

Secondly, the situation could lead to growth of an anti-US bloc that comprises Central Asia as well as both its regional hegemons. Russia has expressed support for China’s stance vis-à-vis the US on this issue, and the joint desire to see a reduction of American influence in the Far East could lead to greater partnership between the two countries that have long been sceptical of the US-led normative order. Indeed, in a recent conference on Russia-China relations in Moscow, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that Russian-Chinese co-operation would continue to grow, and ‘promote justice and equality around the world’, a statement that can also be read as a challenge to US hegemony.

Further, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, comprising China, Russia and all post-Soviet Central Asian states bar Turkmenistan, has unanimously supported the Chinese stance in the South China Sea. Without directly naming the US, it issued a statement declaring that outside intervention in the matter is strongly opposed by the organization. The SCO is often perceived by Western observers as a legitimating tool for China’s activities in Central Asia; its endorsement of China’s position in the South China Sea demonstrates the organization’s use as a legitimating tool for other aspects of Chinese foreign policy as well.

Chinese efforts to control the South China Sea is in large part about image, a demonstration to the world that it is a major power capable of rebuffing the US. If it is unable to fulfil this image in that context, it stands to reason that it will look elsewhere. Central Asia presents itself as a prime location for this endeavour: China may construct grand infrastructural projects with willing partners, aggregating anti-US sentiment at the same time.